Proud gardener Les Cook shows off the tomatoes and rhubarb he grows in his suburban Canberra backyard. Picture courtesy Canberra Times.

Raised in rural Victoria before heading off to war, LES COOK hasn’t even visited Cape York, let alone lived here. So why is his story relevant to readers?The truth is that his story is relevant to every Australian. The 99-year-old sat down with Cape York Weekly editor MATT NICHOLLSin February to share his story …

WE could all learn a thing or two from humble war hero Les Cook.

The top-shelf gardener, proud dad and gym regular is still living his best life in a quiet suburb near the Canberra Hospital.

Earlier this year I found myself in the nation’s capital at the historic Australian War Memorial and had a lightbulb moment – for Anzac Day this year I should write a piece on a World War II veteran.

So I did some research, made a few calls and emails and stumbled upon Les.

The interview was set up by his wonderful daughter Debbie and my partner Emily and I lobbed up to his house on a sunny morning in early February.

I remember thinking as I drove to his house how hard it would be to interview a man who had lived such a long and meaningful life.

For a 99-year-old, Les was full of beans and we sat in his backyard drinking coffee, chewing the fat and discussing some of his vivid memories from wartime.

The only instruction I was given by Debbie was not to try and upset him – a TV crew had interviewed Les a few years earlier and pushed him to exhaustion trying to get him to be emotional on camera.

For me, that was an easy request as I didn’t want to talk to him about the worst of the war.

I was eager to learn about how life had changed for Les and his mates when he came home and what Australia was like in the post-war era.

We got sidetracked a few times but I walked away in awe.

FAMILY DUTY

THE first thing you need to know about Les Cook’s war experience is that he didn’t have to serve.

He was 17 when he enlisted in May 1940 and you had to be at least 20 or 21 at the time.

His father Ernest, who served in the First World War, also lied about his age, telling recruiters he was several years younger so he could enlist again.

“You could have said your name was Ned Kelly,” said Les.

“You didn’t need any evidence. We both enlisted under our own names and I’ve always thought that mum could’ve rung up and had us kicked out, but she knew we would’ve just gone and enlisted under a different name.

“We felt that we had a responsibility to support the stand.”

Les Cook hopes to get a letter from Queen Elizabeth II, not Prince Charles. Picture courtesy ABC Canberra.

Les’ father actually served for two armies. He was first in the British Expeditionary Force and joined the Australian Imperial Force for World War II.

“I was born in England and my second birthday was on the boat (to Australia),” Les said.

He was 16 years old when he first tried to enlist after the war broke out in 1939.

“I think they said ‘go and try the boy scouts’,” Les recalled.

It wasn’t until after the battle of Dunkirk in that he was finally successful in joining the army.

“It was the thing to do in our generation,” he said.

“I remember when I left work, the head of the organisation talked of courage, and I remember saying at the time, it would have taken more courage for me not to have enlisted.”

DEPLOYMENT

IF circumstances were different, Les would have a passport to be envious of.

He shipped off to North Africa and did stints in Greece, Crete and Syria. He came back to Australia for six months before his unit was sent to New Guinea to try and stop the Japanese advance on Port Moresby.

Having survived that and a trip to Borneo – as well as a second bout of malaria – Les didn’t stop serving when the war was declared over in 1945.

He volunteered to go to Japan in a peacekeeping-type role and was discharged from the army in 1947.

Ask those who know him and Les was a fine soldier who served his country with pride and honour.

But ask Les and he’ll play down his role, shouldering arms to any questions that paint him as a hero.

“It’s embarrassing to be held up as something that you’re not,” he said.

“As one man said, we weren’t soldiers, we were heavily-armed civilians – and I liked that definition – because that’s what we were.

“We were just ordinary people. Yes, there were some who were heroic and some who were extraordinary, but for the most part, we were just ordinary people, and, just like in life today, some of us were just making up the numbers.”

Max Caldwell and Les Cook at a gathering of the 2/14th Battalion 2nd AIF.

While Les believes Anzac Day is an important day and attends services with pride, he doesn’t believe he deserves special praise.

“When I go to these services, I think, ‘They’re talking about you’,” he said.

“We were just the generation that happened to be alive at the time. People ask me, ‘What did you do in the war?’ and I tell them, ‘I walked among kings’.”

As we sat in the sun on a mild Canberra morning, I told Les the story of my grandfather’s uncle, the late Corporal Tom Fletcher who signed up to be a medic in the same war because he wanted to serve but didn’t want to kill.

Tom served alongside the inspirational Corporal John Metson, who crawled in agony down the Kokoda Track for three weeks after he was shot in the ankle.

Metson refused to be stretchered because he didn’t want his mates to carry him, so bandaged up his hands and knees and crawled through the jungle.

My grandfather’s uncle was left in a New Guinea village to look after the wounded men while those who were fit enough pushed on for reinforcements.

Before help arrived they were discovered by the Japanese forces.

Unarmed, they were brutally killed then and there.

“That story will tell you more about the war than I ever could,” said Les, who has written about Metson and his crew and speaks highly of their bravery. Still, he prefers to remember the fonder and funnier times at war.

“In Borneo, we were cut off for three days and two nights and we didn’t get much sleep,” he said.

“There were two blokes in a shell hole that was half full of water. One of the blokes went to sleep and his steel helmet pushed his head under the water.

“The other bloke heard him breathing bubbles under the water and pulled his head up.

“Another time a bullet came past an officer’s head.

“The officer turned around and yelled out: ‘Look out where you’re firing, you nearly hit me.’

“And the bloke said to him: ‘There were two Japs the other side of the tree you were behind, and I’ve just shot one of them.’”

BEFORE AND AFTER

LIFE was certainly no picnic for a young Les Cook.

He grew up on a dairy farm in the Gippsland region in south-east Victoria and had a rifle in his hands when he was seven.

Two years of secondary school was all that was required before he landed a job with the railways.

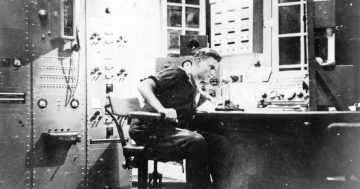

“You got an extra sixpence a day if you learnt Morse code so I did,” he said as he talked about how he started as a signaller for the army when he first enlisted.

“That wasn’t what I signed up for and later I was carrying an anti-tank rifle and in Syria, I carried the Bren gun, the anti-aircraft machine gun.”

When he returned from Japan in 1947, he caught the train from Sydney to Melbourne to make a new home for himself after seven years of service.

He signed up single but had an inkling he had someone special waiting for him in Melbourne.

Les first saw Betty on the train in a rare stint back in Australia between his Middle East tour and his pending New Guinea mission.

He had been in hospital and was preparing to be permanently discharged when he spotted Betty on the Hampton line.

“He didn’t have the courage to talk to her on the first day but thought if he was on the same train the following day he might have a chance to see her,” said daughter Deb, who made sure her father didn’t leave out any good bits.

As Les recalled: “She lived in the same suburb (Hampton) and I walked her home.

“We talked for about an hour and exchanged details.

“When I went (to New Guinea) we hadn’t even held hands. But she’d write to me and we wrote for about three years.”

He recalls telephoning Betty when arriving in Melbourne.

“I would have still been in my uniform because I didn’t have any other clothes,” he said.

Reunited in person, they married the following year and had their honeymoon in Cairns.

They went on to raise three daughters – Annette, Judy and Debbie and spent most of their life in Canberra.

“I was offered my old job back at the railway but I wanted a job that kept me outdoors,” Les said.

He took up carpentry but as the nation struggled in the post-war era, he decided that a government job would be best for raising a family.

He accepted a position with the Commonwealth in Melbourne and later transferred to Canberra, working in geoscience.

Every day he would return home for lunch to be with Betty, who was a homemaker without a network in the capital.

“We had a happy marriage. We were friends as well as lovers,” he said with a tremble in his voice.

He looked after his wife until the end.

EYEING A CENTURY

YOU can’t help but admire Les’ attitude towards life.

His house is tidy, his garden full of fruit and vegetables and his zest for living is steadfast.

“I still go to the gym, you know,” he beamed at me, probably hinting that I should be taking a leaf out of his book (he’s right).

“For my 99th birthday the gym gave me a life membership!

“I’m hoping I can get a bit out of them.”

Les will turn 100 on January 10 next year, although his service record says he has already hit the milestone.

He hopes Queen Elizabeth II will still be alive to write him a letter for his birthday.

“For the 75th anniversary there were eight of us sent up to New Guinea and Prince Charles and Camilla were staying in the same hotel,” Les said.

“Camilla came and talked to us for about an hour, but Charles is … different.

“If I make it to 100 I hope the Queen is still there.”

ANZAC DAY

WHILE Les believes the days of him and his World War II mates are numbered at Anzac Day ceremonies, he isn’t worried that the commemorations will drop off in the future.

“The young people are showing so much interest in it. They don’t need any push to do so,” he said.

“It’s a very significant day. There’s no doubt about that.”

In a piece he wrote not too long ago, Les penned: “When you stand in silent remembrance on Anzac Day, or when you stand before a cenotaph or at the gates of a war cemetery and read the words, ‘Their name liveth for evermore’, think of John Metson; of his fortitude, his determination not to be a burden to others, and his cheerful acceptance of the awful situation into which he had been thrust.”